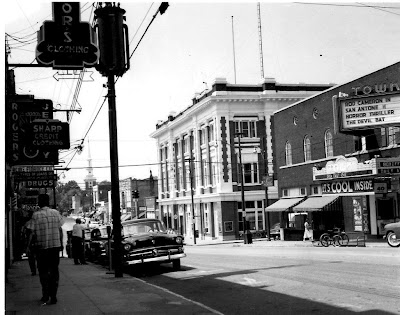

This photo by Don Bolden, which must have been taken just about the year we moved to Burlington, shows the Town Theater’s enticing “It’s COOL Inside” banner. The building on the next corner is the old City Hall, which has been demolished. In the distance is Front Street Methodist Church.

My family moved to Burlington from Galax, Virginia in 1954. We were very familiar with Burlington because my mother’s family had moved there from Caswell County during the Depression and my parents had met there. My father, who was a native of Randolph County, was an office manager for Burlington Mills -- his only employer from the time he graduated from high school in 1930 until he retired 47 years later – which had transferred him to Galax in the late 1930s. He quickly decided that Galax was no place for a bachelor.

After my parents were married in the First Baptist Church in Burlington just before Christmas, 1939, they set up housekeeping in Galax. At first they lived in a series of basement and garage apartments, all of which my mother would later describe as very Spartan. By the time my mother was pregnant with me in 1944, however, they were living in a house rented from a couple named Moore with whom they had become friends. Mr. Moore, who also worked for Burlington Mills, had been drafted and his wife had gone back to her hometown in another state to wait out the duration of the war, so they turned their house over to my parents. Given the acute shortage of housing in Galax during World War II this was a great stroke of luck. Because Galax had no hospital, my father sent my mother back to Burlington to await my arrival, which is why I am “a Tar Heel born” rather than a native Virginian. I was born at the old Alamance Memorial Hospital on Rainey Street on August 29, 1944, but spent my first ten years in Galax.

My mother’s parents, both of her brothers, and one of her sisters lived in or near Burlington, so we made regular visits when I was a youngster. I sometimes spent a week or two in the summer visiting with my first cousin Lynn Smith, whose family lived on St. John Street a few doors from my grandparents.[1] Consequently, when my parents moved back to the city in the spring of 1954 I came to a place that was not completely strange to me. My parents rented a little house at 318 Highland Avenue where we were to live while they built a new house across town.

One thing that I expected I would not like about Burlington was the summer heat, which I had experienced during my visits. Galax sits at about 2500 feet above sea level, in a valley of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Although it certainly experienced hot summer days, they were relatively few and infrequent, and the nights generally were cool and pleasant. Burlington seemed sultry by comparison. Whereas I usually slept under a light blanket at home, I had vivid memories of sleeping, or trying to sleep, at my cousin’s house while lying on top of the bed clothes in my underwear with an oscillating electric fan blowing on my sweaty body. My expectations and fears were borne out soon after we moved; in June of 1954 the thermometer hit 100 degrees several days in a row. My mother repeatedly said of our little rental house, “This place is like an oven.” (Actually, “sauna” would have been a better metaphor, but at that point in our lives none of us had ever heard of such a thing.)

In those days almost no homes, and few businesses, had air conditioning. May Memorial Library, which did, quickly became one of my favorite places, and would have even had I not been a voracious reader. Like most major churches, First Baptist, which we attended, was air conditioned, as was Sellars’ department store and Burlington’s two movie theaters – the Paramount and the Town. The Paramount was the classier of the two, but the Town, on Front Street, was where Lynn, our neighborhood friends and I went on Saturday mornings to cool off and enjoy the weekly “kiddie show,” which usually included several cartoons, a western (Lash LaRue, the “King of the Bullwhip,” was a favorite), a comedy featuring Abbott and Costello or Huntz Hall and the Bowery Boys, and one or two serials, each episode of which had a cliffhanger ending.

In early afternoon we would emerge blinking into the heat and head straight for Zack’s, a hot dog stand steps from the theater. Zack’s, the official name of which was the Alamance Hot Wiener Lunch, is still in existence. Having been run by the Touloupas family since 1928, it was and is a classic example of the Greek-owned hot dog stands and short-order restaurants that you could find in any North Carolina town of any size in the 1950s. Several, including Dick’s Hot Dogs in Wilson and the Roast Grill in Raleigh, are still in operation. (You can read a history of Zack’s, and see historic photographs, here: http://www.zackshotdogs.com/portal/History.aspx .)

What we went to Zack’s for in 1954 are what you go there for today: traditional Southern style hot dogs featuring a grilled wiener in a steamed bun topped with mustard, chili and either slaw or onions (or both). If Lynn and I were together, as we usually were, one of us would have a dollar for our lunch. The hot dogs were 15 cents each, so we would order six. The ritual involved in dispensing them was endlessly fascinating. The counter man, who in those days usually was John Touloupas, would pull six warm buns from the steamer, put a grilled hot dog in each, and line them up from on his left arm from hand to elbow. Mustard was swiftly applied with a wooden stick and chili with a wooden spoon, followed by your choice of slaw and/or onions. Then, in a feat of legerdemain at which I still marvel, he would deftly remove each “dog” from his arm and, using only his right hand, wrap it in onionskin paper and put it into a paper bag.

We paid and left the store, each carrying a bag (or, to use our terminology, a “paper sack”) containing three extraordinarily odorous and greasy hot dogs. Our destination was a little grocery and service station that our grandfather, W. L. Smith, operated on the corner of Holt and North Main streets; our goal was to get there before the grease from the hot dogs ate the bottoms out of the paper sacks.

Our “Paw-Paw,” who was known as “Smitty” to his friends and patrons like Paul “Hardrock” Simpson, Burlington’s legendary “running postman,” had been a merchant his entire adult life. My mother said he kept his little corner store primarily “to have something to do” after my grandmother died in 1950. His store had a single Sinclair gas pump, the access to which had been created by “cutting off the corner” of the building’s first floor to create a triangular overhang. Patrons drove their cars into the space from one street and exited into the other. As a consequence of this arrangement, the tiny store itself also was triangular. Its interior was dominated by a glass-fronted case displaying “Mary Janes,” “Bit O’ Honeys,” “Bulls Eyes,” “Fireballs” and other kinds of penny candy. The case also held “Tootsie Rolls,” “Baby Ruths” and many other kinds of candy bars, as well as chewing gum, “Bazooka” bubblegum, and candy cigarettes (which our parents forbade us to buy). In summer there was a box of bubblegum pieces, each of which was enclosed in a wrapper that also contained a baseball player’s card. The store also offered an eclectic array of useful everyday items ranging from cigarettes and matches to bread and Vienna Sausage.

Outside the store, under the overhang, were an ice cream box and two large “chill boxes,” or refrigerated chests, of soft drinks – one red, for the drinks delivered by the Coca-Cola route man, and the other blue, for Pepsi products. Lifting the four lids on the ice cream box revealed an array of frozen treasures. Beneath one were popsicles in various colors and flavors and other concoctions on wooded sticks, including “Brown Mules,” “Fudgsicles,” and “Dreamsicles.” Another compartment contained “Dixie cups” in various flavors, while a third was the place to look for an ice cream sandwich, a “Nutty Buddy,” or a “Push-Up.” The fourth held pints and half gallons.

In addition to Cokes and Pepsis, the drink boxes dispensed Orange Crush (my personal favorite), Nu-Grape soda, Seven-Up, Cheerwine, ginger ale, two or three brands of root beer, and Yoo-Hoo, a chocolate drink for which I could never acquire a taste despite its being endorsed by Yogi Berra, one of my baseball heroes. In the chill boxes, which were also known as “sliders” because of the way they operated, the bottles sat in cold water in rows with their necks protruding up through metal guides. A coin-operated mechanism allowed patrons to slide the soft drink of their choice along the guides and lift it out through a kind of gate, which promptly closed. Paw-Paw sometimes allowed us to fill the drink boxes and empty the “cap catchers” attached to the bottle openers.

Alongside the soft drink chillers and the ice cream chest were two or three slightly dilapidated wooden chairs. Our grandfather, who always wore a sweat-stained grey fedora, often sat in one chatting with men from the neighborhood while he waited for the next customer. If all the chairs were occupied a patron could join the conversation by turning a wooden soft drink crate up onto its end and sitting on it.

I guess “Smitty’s” was a good place for old men to sit and swap yarns; for sure it was an especially good place for a young boy to sit and eat hot dogs and drink an Orange Crush on a hot summer afternoon.

[1] Lynn, who was a year younger than me, became an excellent baseball player. He played third base for WHS and for East Carolina University in the 1960s.